Improving Technique, Improving Technology

This article was written by Ramon Ripoll Masferrer

Ramon Ripoll Masferrer is an architect and holds a PhD from the Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC)

The distinction between technique and technology allows for interesting interpretations. Especially if we understand technique as the set of means to materially transform the world, and technology as a technique that also has cultural objectives. Thus, technology possesses the intention of visible physical well-being, inherent to technique, but also has invisible psychic intentionality. Therefore, technique is pragmatic (1), and technology is pragmatic and humanistic (2).Accepting this distinction, we see that technical progress is measured mainly by scientific, productive, and economic parameters, and its goal is primarily physical well-being. Technological progress shares the same objectives as technique, but cultural, linguistic, and emotional parameters must also be considered, aiming at both physical and mental well-being.What is most surprising is that throughout human history, technique and culture have always coexisted in balance. This stability and harmony persisted until the industrial period. It is especially during the 20th century that the field of technicism, colloquially speaking, experienced exponential growth to the present day, while the cultural field lagged behind with minimal evolution. This created a significant split between science and culture.Today, humans have access to all kinds of technical tools, products, and means to act, transform, and improve the well-being of their external world, but very few technological tools for personal, emotional maturation and the well-being of their internal or affective world.This important distinction allows us to clarify the purpose of this article: to denounce the imbalance between technique and technology.

Improving Technique

This first part, advocating more technique to make material progress accessible to everyone, is highly relevant. The main goal of technique should be to promote equal opportunities for all humans. The democratization of technique is the current major guarantee justifying material progress, enabling access to knowledge, services, and social mobility for as many individuals as possible.Technique should be accessible to everyone, all families, communities, and nations, particularly the underserved, breaking the monopolies of large companies that regulate, commercialize, and speculate on technical progress, turning essential high-tech products into items only affordable to the wealthiest.These large concentrations of power act solely for economic interests, never social ones.

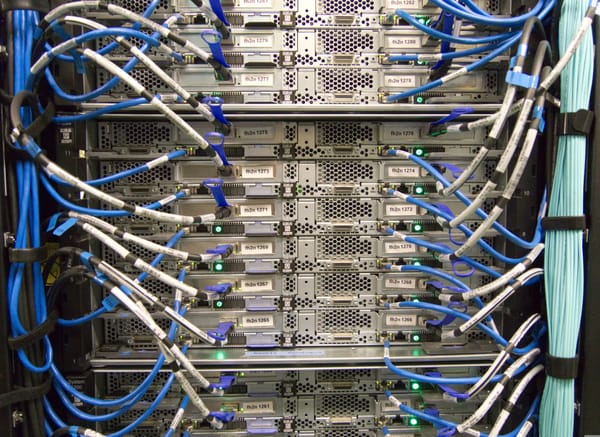

Situations of technical totalitarianism must be avoided, fought, and denounced. For example, the unfair competition of indispensable, highly technical products. NVIDIA’s recent consolidation of technological dominance through a software ecosystem creating dependency illustrates this. Its lock-in strategy allows high price control, with AI GPUs like the H100 exceeding $30,000–$40,000 each, unfairly reinforcing leadership in AI accelerators and reducing market competition. Extremely high profit margins reflect this dominance. International regulation is needed to prohibit practices limiting free competition and raising costs, counteracting progress democratization.

Fortunately, innovation exists outside highly technologized multinationals. Young talent and small start-ups frequently contribute extraordinary developments. Recent R&D, seemingly minor, achieved pivotal results. Proactive individuals, anonymous talent incubators, and next-gen start-ups cover all technical fields, from theoretical and sensitive areas like AI to practical necessities like energy storage batteries.Example: 41-year-old Chinese engineer, founder of DeepSeek (2023), with 160 employees, amazed with open-source generative AI proposals. Finnish engineer Marko Lehtimäki, founder of Donut Lab (2024), with 100 employees, unexpectedly developed a solid-state battery with much higher energy density, faster charging, and greater durability than current lithium-ion batteries, almost doubling energy density.

Young individuals and start-ups capable of significant contributions from nearly nothing, with competitive, open, high-value proposals, demonstrate that breaking monopolies and fostering diversity is essential for future technical progress and addressing major social and economic challenges.States should promote open, rigorous, and diversified innovation with egalitarian, realistic, and practical criteria, avoiding speculative investments, while supporting entrepreneurship, initiative, and technical ingenuity across educational and professional spheres, combining method and technical rigor with creativity.

Improving Technology

All of the above is relevant, but even more crucial is combining technique with humanism. This pending task requires promoting technology alongside culture applied to technique, bridging two currently antagonistic domains.Previously, preserving technique from corporate monopoly was clear; now, preserving it from exclusivity for the sake of progress or materialistic technique is essential. Technique should not be mere functionalism for consumption-driven capitalism, promoting rampant consumerism of high-tech products. This harms democratization and deep humanization, preventing technique from serving human dignity, humanized freedom, critical thought, and comprehensive personal development. Technical alienation must be avoided.

Fortunately, positive examples of technological humanism exist across disciplines, especially architecture. Designs prioritize humanized, functional spaces with natural light, human scale, and nature integration.Example: 20th-century Finnish architect Alvar Aalto pioneered organic architecture, humanizing spaces by combining functionalism, organic forms, new techniques, and natural materials. He innovated with steam-bent laminated wood for freer organic shapes while enabling mechanized industrial production, adapting structures and materials to Nordic climates, addressing both material and deeply human needs and emotions (4).

Studying technique from a humanistic perspective is increasingly difficult but essential, to humanize the whirlwind of rapid technical evolution and prevent it from mechanizing or silencing human emotions. Reharmonizing science and culture requires solutions to make technique provide comprehensive, anthropomorphic service, thus becoming technology: technology serving humans, their needs, and deepest values, designed to improve life without replacing or dominating it.

Hopefully, in a few years, we can be proud of a technique that is not only socially democratizing, promoting human rights and equal opportunities, but also becomes true technology capable of loving humans as they need to be loved.

(1) Richard McKay Rorty, 20th-century American philosopher, associated with pragmatism and postmodern thought, does not believe in absolute truth, but simply in coexistence and democratic progress: "The pragmatist defends the survival of a culture without Philosophy, without attempting to separate contingent and conventional truths from those that go beyond." (RORTY, Richard (1982). Consequences of Pragmatism. Madrid: Editorial Tecnos, p. 51)

(2) Erwin Schrödinger, Nobel Prize in Physics 1933, key in the development of quantum mechanics with his famous wave equation, warned: "I doubt that humanity’s happiness has increased thanks to the technical and industrial advances brought about by the rapid growth of natural science." (SCHRÖDINGER, Erwin (1998): Science and Humanism. Tusquets Editores, p. 13)

(3) Francisco Rico, Professor of Medieval Hispanic Literatures at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, defines humanism as love for the human being and defends humanized arts and sciences: "The foundation of all culture should be sought in the arts of language. Antiquity was a dream, as the means never managed to achieve the end." (RICO, Francisco (2002): La Mano. The Dream of Humanism. From Petrarch to Erasmus. Destino, Barcelona, p. 19)

(4) Alvar Aalto, 20th-century Finnish architect, of great importance for humanizing architecture by combining functionalism, organic forms, natural materials, and attention to human well-being: "Architecture is not a science. Architecture is the great synthetic process of combining thousands of defined human functions. The purpose of architecture is to harmonize the material world with human life." (AALTO, Alvar (1977): The Humanization of Architecture. Tusquets Editores, Barcelona, p. 29)